Embracing Change

A Multiliteracies Approach

"[Multiliteracies] are energizing for both students and educators because they offer opportunities for creative and critical engagement" (Gouthro & Holloway, 2013, p. 51).

Multiliteracies

What are

Multiliteracies?

Why implement

Multiliteracies?

How can we

create

multiliteracies

classrooms?

What are Multiliteracies?

"The multiliteracies approach suggests a pedagogy for active citizenship, centred on learners as agents in their own knowledge processes, capable of contributing their own as well as negotiating the differences between one community and the next" Cope & Kalantzis, 2009, p. 172).

Multiliteracies is a framework that includes four main components of Overt Instruction, Situated Practice, Transformed Practice and Critical Framing. Educators may view it as a method of organizing known effective strategies and implementing new 21st-century literacies. Cope & Kalantzis (2008) posit that the "Multiliteracies Framework aims to supplement - not critique or negate various existing practices" (p. 207). Gouthro and Holloway (2013) explain that "multiliteracies pedagogies draw upon artistic, technological, and cultural resources to develop innovative and creative approaches to teaching and learning" (p. 53). Lavoie, Mark, and Jenniss (2014) describe Multiliteracies as "developing skills that are in line with literacy needs so that all new knowledge is transferable and long lasting" (p.213). To provide an overview of the concepts I have created a chart with a brief description of each of the four components, student evidence of learning in that particular frame, and a classroom example.

Description Evidence Classroom Example

Overt

Instruction

"involves systematic, analytical, and conscious understanding" (Cope & Kalantzis, 2008, p. 206)

Students are able to effectively describe what they know.

When reading a text, at their level, the student is able to describe the strategies they use to help understand unknown words.

Situated

Practice

"involves immersion in the experience ... including those from the students' lifewords" (Cope & Kalantzis, 2008, p. 206).

Students demonstrate their understanding by applying what they know to problem-solving with or without teacher or peer support.

Following a student's presentation of a self-authored book, all students are motivated to write their own book. While writing, several students realized the limitations of their literacy skills so they asked for scribed support from home. Others wrote sentences and included detailed illustrations to best represent their story.

Transformed

Practice

"involves applying a given Design in a different context, or making a new Design" (Cope & Kalantzis, 2008, p. 206).

Students will add their own ideas to create something new as a result of their learning or transfer their understanding to new or different areas.

A student applies what they learned from authoring a book to create a poster in media literacy that describes (in print and image) the steps to correct hand washing.

Critical

Framing

"involves the students standing back from the meanings they are studying and viewing them critically in relation to their context" (Cope & Kalantzis, 2008, p. 206).

Students will question the event using their intellect and experience .

While reading a non-fiction text on birds of prey, the student disagrees with the author's statement of the largest bird of prey using his experience and previous readings on this topic.

Incorporating the Multiliteracies pedagogy in my grade one class has given me context and guidance with how I can best engage and create meaningful learning for the 21st-century student. Giampapa (2010) states "a multiliteracies pedagogy maps out how pedagogic design that includes Situated Practice, Overt Instruction, Critical Framing, and Transformed Practice can create learning opportunities for all students" (p. 410). It has certainly been my experience in that creating a stage where students share their personal interests and inspire each other through their life events (Situated Practice), blend their classroom knowledge (Overt Instruction), and build, write or create something new (Transformed Practice), results in a more highly engaged and motivated student. When I provide the opportunity for students to share a personal design, I also provide a bridge between home and school by valuing their interests and then connecting these motivations to the curriculum. In giving the student time and space to share, I demonstrate to all students that I am interested in their activities and value their events and opinions (Critical Framing). There has been a significant increase in energy and excitement in our classroom by framing my instructional day with Multiliteracies.

Why implement Multiliteracies?

"Despite recognition for the changing shape of literacy, a gap continues in how curriculum and pedagogies in Canadian schools prepare students for the challenges of the new economy" (Giampapa, 2010, p. 411).

How our society communicates with each other and with the world has greatly changed in the twenty years I have been an educator and in the last six years, this change has been rapid. There are early years students who have had experience with digital literacies including interactive games and communicating through text either with print or emojis. Giampapa (2010) supports this digital reality when he posits "the importance of creating learning environments to engage students in a wide range of literacy practices that are creative and cognitively challenging and that bring together text-based and multimedia forms of meaning making" (p. 410). By implementing the Multiliteracies approach teachers are bridging the traditional school-based literacies with those that students actively participate in outside of school.

Traditionally, classrooms have taught literacy as reading, writing, oral communications, and media literacy. However, as Cope and Kalantzis (2009) explain "the new media mix modes more powerfully than was culturally the norm and even technically possible in the earlier modernity that was dominated by the book and printed page" (p. 178). Good teaching now needs to incorporate a variety of modalities (e.g., visual, audio and gestural representation), as the scope of what it means to be literate today greatly differs from that even of the recent past (Cope & Kalantzis, 2009). As students are digitally expressing their thoughts, ideas, and daily events, teachers need to acknowledge this new literacy and blend the new with traditional reading and writing. Cope & Kalantzis (2009) support this when they describe that "with these new communication practices, new literacies have emerged" (p. 167). If teachers are to foster Multiliteracies in their classrooms, their students will be afforded the opportunity to be lifelong learners (Gouthro & Holloway, 2009, p. 59). Simply put, unless we embrace digital literacies, provide students a classroom culture that values their voice and challenges them to think critically we fail to provide 21st-century students with an education that is meaningful.

How can we begin to create Multiliteracies Classrooms?

"If education for the twenty-first century is to prepare students to deal with the new demands on literacies and the rapidly changing technological terrain, then educators should invest in students' multiliteracies and multilingual identities as resources inside classrooms and schools" (Giampapa, 2010, p. 426).

I have blended theory and personal practice to provide examples of each of the four components of the Multiliteracies framework. My hope is that parents, teachers, and administrators can make connections from my reflections to their own experiences in the classroom and therefore develop a practical understanding of how to begin to implement Multiliteracies for their students.

Overt Instruction

Overt Instruction can also be considered "conceptualizing". Cope and Kalantzis (2009) describe conceptualizing as "a knowledge process in which the learners become active conceptualizers, making the tacit explicit and generalizing from the particular" (p. 185). Once instruction occurs within each student's zone of proximal development, the student should be able to demonstrate their understanding in new or different ways. Mills (2010) posits that "Vygotsky convincingly argued that adults should bridge the distance between learners current levels of understanding and levels that can be achieved through collaboration with experts and powerful artifacts" (p. 38). At the grade one level, I have found using student artifacts from home or from our environment creates the most meaningful connection and learning opportunities for students.

This component of the Multiliteracies framework was the easiest one for me to assimilate into my classroom instruction. It was simple to turn the responsibility of students writing the morning message, allow more time for student conversations during large and small group discussions, and implement the multimodal sound cards to improve reading and writing skills. I agree with Cummins et al. (2005) that "when students take ownership of their learning - when they invest their identities in learning outcomes - active learning takes place" (p.1). Below, are a few visual examples of Overt Instruction in the grade one classroom. For a more in-depth description of

each of the examples, please click on the link to

Morning Message

Multimodal Resource

Large and Small Group Instruction

Situated Practice

A good example of this was when the grade one parents took photos of something pivotal on the weekend and texted it to me on the Class DOJO app. On Monday morning, I would show the image on the SmartBoard and the student would orally share this event with the class. Students were excited and motivated to share images of completed puzzles, tall 3-D structures, and lego creations. Often, students would ask the presenting student questions about their photo and an authentic Transformed Practice exchange would occur (students were learning how to create something new from something known such as a lego action figure). There was particular interest when students showed pictures of structures. As the classroom teacher, this interest sparked me to create a maker space for students to build and create in a free and creative manner.

The second segment of Situated Practice is experiencing the new and Cope and Kalantzis (2009) describe this as being "exposed to new information, experiences and texts, but only within the zone of intelligibility and safety, sufficiently close to their own life-worlds" (p. 185). In the chart above, under Classroom Examples, I describe a class-wide book writing event that was initiated by one student sharing their own authored text. It was important, as the classroom teacher, to support students in their literacy zone of development so that the student could experience a personal challenge but also minimize any levels of frustration that may emerge. Also, equally important is that the approaches used in the classroom (e.g., gradual release of responsibility, collaboration, peer support) reflect the specific culture of the classroom, school, and community (Learning for All, 2013). Below, are some visual examples of our grade one Situated Practice.

The Multiliteracies framework of Situated Practice has been a catalyst for academic motivation growth and excitement in grade one. Of all four components, this area has influenced my daily teaching the most. Situated Practice can also be described as experiencing the known and experiencing the new (Cope & Kalantzis, 2009). Experiencing the known involves "reflecting on our own experiences, interests, perspectives, familiar forms of expression and ways of representing the world in one's own understanding" (Cope & Kalantzis, 2009, p. 185). Providing all students with the time and space (see our class stage below) to share their own experiences led to many original events in grade one.

Our Class Stage to Share Artifacts Class Authored Books A Student Sharing on Class DOJO

Transformed Practice

To transform your practice means to bring your knowledge and understanding in one realm and apply it to another. It may also be referred to as "applying" something from a student's classroom experiences to the "real world" (Cope & Kalantzis, 2009). Transformed Practice "involves making an intervention in the world which is truly innovative and creative and which brings to bear the learner's interests, experiences and aspirations" (Cope & Kalantzis, 2009, p. 186). This area was the most challenging for me to implement as I had to break away from encouraging students to follow a class model and instead open my practice to accept a variety of designs that were personally meaningful for the student.

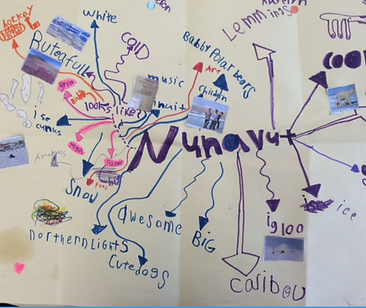

An example of this challenge was a mind map I asked the students to create, in small groups, on the topic of Nunavut. After discussing the task and working as a class to begin a mind map students went off in their groups to create their own map. Their completed maps seemed disorganized and difficult to read and understand. I was very tempted to have all groups re-create their map, but then I reflected on how I could make this event meaningful from a student perspective. Rather than having students conform to my expectations, I provided several different visual images of Nunavut and then required them to read their posters and add each image to the corresponding printed text. As Gouthro and Holloway (2013) describe, "its all about creating something new out of something learned" (p. 64). Their new maps were meaningful to them - an enriched and authentic literacy event.

Print and Image Mind Map of Nunavut

Critical Framing

Another way to consider the framework of Critical Framing is to be analytical. Cope and Kalantzis (2009) describe this component of Multiliteracies as "learners explore causes and effects, develop chains of reasoning and explain patterns in text" (p. 186). To begin to encourage students to think critically, I utilize our read aloud time to open discussions of the author's message such as acceptance, friendship, courage, and fairness.

As Gouthro and Holloway (2009) suggest, "if we are to prepare teachers to educate their students to participate actively as citizens, this requires that they work through difficult and conflicting ethical considerations, such as what they think is right and fair, and what will promote genuine democratic processes" (p. 53). With consistent exposure and questioning, teachers can motivate students to think on their own and derive meaning from text with some guidance while refraining from sharing their own perspective. I encourage students to use specific examples from the text to support their perspective of the author's message.

The Author's Message in Read Aloud Text